Digitizing the Battlefield

Practical AI for Tactical C2

In my last post, I talked about my three rules for judging whether an AI project is worth pursuing. This one puts those rules into practice.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning are born from data — whether painstakingly hand-labeled images or terabytes of text scraped from the web. Modern tech companies obsess over data collection because models improve most when data streams are constant, granular, and frictionless.

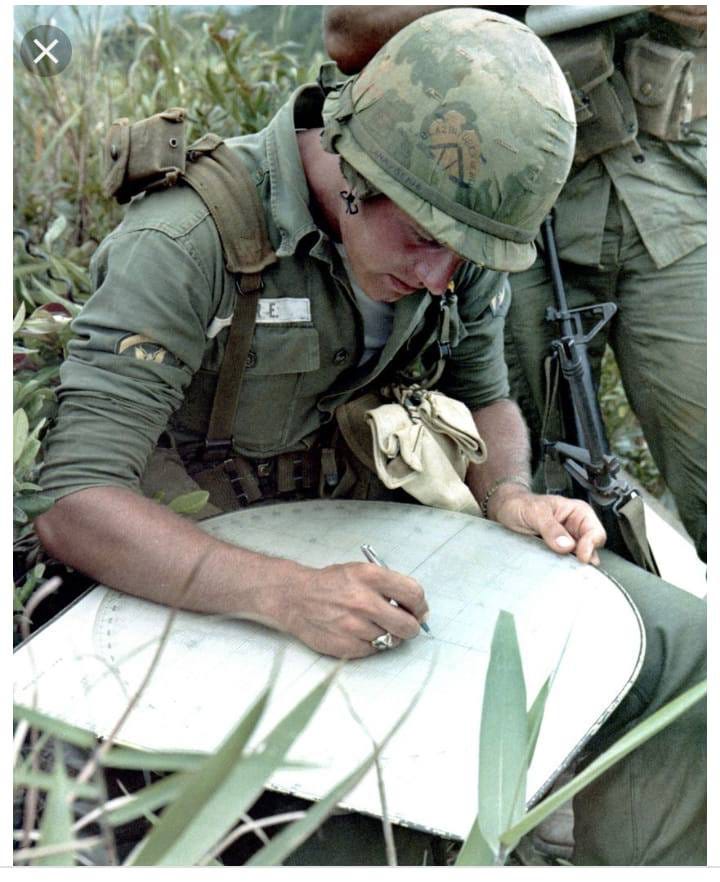

The Army’s tactical data pipeline, by contrast, is often analog: voice calls, hand-written notes, and ephemeral logs that vanish at the end of an exercise or rotation. The first step in integrating AI on the battlefield is digitizing information at its source—then deciding what to do with it.

How tactical reporting actually happens

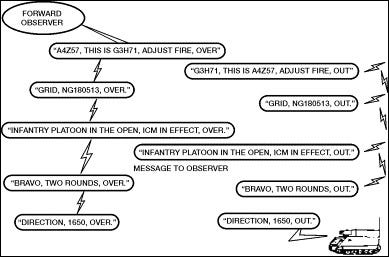

Imagine a forward observer unit spotting an enemy platoon and calling for mortar fire. A typical exchange sounds like this:

This exchange takes about sixty seconds. The words are encrypted, but the radio’s electromagnetic signature is not. Long transmissions light up the spectrum and invite detection. Voice is also bandwidth-heavy: an MP3 of the call might be megabytes, while the actual information amounts to a few bytes. And there’s no integrity check—if a fragment drops, you just “say again.” Because the traffic is synchronous, a single lost connection stalls the mission. Usually, the only record is whatever gets scribbled in a notebook—if it’s captured at all. The system works, but it’s slow, exposed, and mostly ephemeral, making it a perfect candidate for a digital overhaul.

A practical AI-enabled improvement

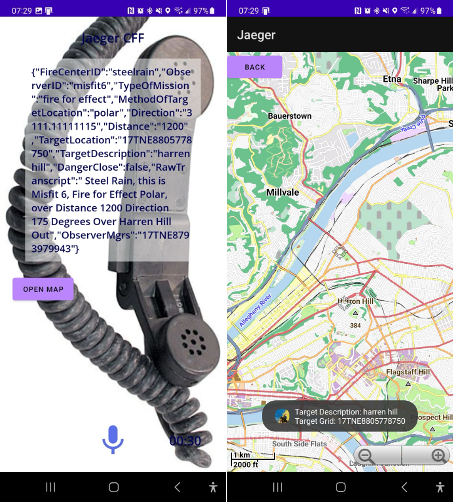

Recent advances in lightweight automated speech recognition (ASR) models—like OpenAI’s Whisper and Meta’s Seamless M4T—mean that accurate speech-to-text can now run on a standard smartphone. The same event—keying a radio—looks different on either side of the wire: one person hears a transmission, another sees a data stream.

For the Tactician:

When you key the radio, the phone records, transcribes, and reads the message back for confirmation or correction. Once you approve, the device sends a burst of structured text instead of a long audio stream—shorter, cleaner, and verifiable. When you receive a message like this, you can either read it on your phone or have your phone read it aloud to you.

For the Technologist:

When the push-to-talk event triggers, the smartphone captures the audio stream locally and runs it through an automated speech recognition model (e.g., Whisper or SeamlessM4T) for near-real-time speech-to-text (STT) transcription. The resulting text is passed to a speech synthesis engine for audio confirmation, creating a human-in-the-loop accuracy check. Once validated, the system transmits a compressed, encrypted data packet—either the raw transcript or a parsed message schema—via the radio interface (ATAK or similar). The receiver client renders it as text or text-to-speech output.

The result: dramatically reduced electromagnetic signature, an integrity-checked message, and compact transmissions that are easier to route and store. It’s a little slower in the moment—readback and confirmation add seconds—but the mission can actually finish faster. It’s the difference between ordering a pizza over the phone and tapping it into an app: fewer mistakes, faster delivery. It also means the data only has to be entered once—right where it happens—instead of being copied, retransmitted, or reentered half a dozen times on its way up the chain. And once a call for fire transmissions is digital, we can start treating it like what it really is: a structured request for action.

From Unstructured Voice to Structured Calls for Fire

In software engineering, an API call (short for Application Programming Interface) is how one system formally requests a service from another. It’s not a vague message like “Hey, do this when you can.” It’s a precisely formatted package of information: who’s asking, what they want done, what parameters define the request, and what format the response should take.

When a Soldier keys the mic and sends a call for fire, they’re doing exactly that—just in analog form. A CFF already follows a rigid schema: observer identification, target location, target description, method of engagement, method of fire and control. Each field has an expected structure and meaning. The observer (the client) sends the request to the firing unit (the server), which performs a service—firing artillery—and then sends a response (“Shot out,” “Splash,” “Rounds complete”). The only difference is that the Army’s “API” runs on human speech over radio waves instead of structured data packets.

That makes the problem—and the opportunity—obvious. If we can translate the spoken CFF into structured, machine-readable fields, we can treat it like any other digital API call. On-device NLP or a lightweight fine-tuned model could parse the transcript, populate the required fields, and confirm accuracy by reading them back to the observer before transmission.

That single move — unstructured voice → structured data — unlocks everything.

Mortarmen get tube adjustments computed automatically (distance, azimuth, elevation).

A digital process might be faster and more accurate than a plotting board, which are still used today (my Company has two). Source Higher echelons automatically receive accurate, timestamped, geo-tagged reports.

Multinational coordination is simplified (text translation or standardized fields replace ad-hoc voice translation).

Drones and sensors can push validated mission packets directly into the same feed.

The exact same idea outlined above works for any semi-structured radio call. A MEDEVAC Nine-Line, SALUTE Report, or LACE report are all examples of systems that could easily benefit from the same “transcribe and parse” treatment.

This system is not just speculative. I built a working demonstration product using an existing open-source project and open-source models back in 2023. The hard part is integration and productionization, not invention.

The data flywheel

Every transmission becomes training data: original audio, transcript, corrected transcript, parsed CFF fields, and final disposition. ASR and parsing errors are explicit signals to improve lexicons and models. Corrections and overrides are labeled examples that let systems learn real battlefield language — accents, brevity codes, and local jargon. Each message, correction, and confirmation becomes a training example. The model doesn’t just process the mission—it learns from it.

Not only does a system like the one proposed here collect data that can be used to improve itself, it also collects data for upstream applications. The timing, volume, location, and effects of fire missions is useful information for everything from planning future firing locations to optimizing ammunition distribution. As an analogy, the growth of social media produced entire industries and extremely sophisticated analytical and predictive tools. But all that was upstream of getting users on a platform. Digital transformation doesn’t start at the command post—it starts with systems that Soldiers want to use.

Where AI Actually Begins

The first step toward “AI-enabled” warfare isn’t autonomy or predictive analytics. It’s structure. The real breakthrough isn’t a new algorithm—it’s finally capturing what our radios, drones, and Soldiers already know.

Once voice becomes text and text becomes structure, everything else follows. A drone spotting a convoy doesn’t need to stream a grainy video feed—it can send a data packet: “five vehicles, grid 17TNE 8793 7994, moving north at 40 kilometers per hour.” It’s not valuable because it “uses AI”; it’s valuable because its detections are structured, timestamped, geolocated, and ready for action. When data has shape, intelligence—and advantage—emerge naturally.

That’s the hinge: structure first, intelligence second. But structure alone isn’t enough. As Herbert Simon warned, “an information-processing subsystem… will reduce the net demand on the rest of the organization’s attention only if it…listens and thinks more than it speaks.” In the next post, I’ll explore what comes after digitization—how to use this new flood of structured data, and how we can keep from drowning in it.

The thing that I like about this article is that you are taking the nebulous “AI is going to transform warfare” and you’re operationalizing it in a practical way that I haven’t seen enough people do.

More of this, please.

I think the concept of starting with the soldiers on the ground is extremely useful in thinking about how to integrate these systems.